The Effects of L Carnitine on in Vitro Maturation of Immature Bovine Oocytes

Abstract

L-Carnitine (Lc) acts as an antioxidant that neutralizes free radicals, especially superoxide anions and protects cells against oxidative damage-induced apoptosis, as following ovulation, intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation increases in oocytes, Oocytes exhibit an intracellular defense mechanism against an oxidative attack. This outcome adversely affects fertilization and subsequent embryonic development, thereby increasing the risk of an early miscarriage and abnormal development of offspring. The purpose of this study was to see how adding LC to either maturation or fertilization medium affected the developmental competence of immature bovine oocytes. In this study, Ovaries from apparently normal reproductive organs of cattle were collected within 30 minutes from slaughter and evisceration of animals. Cumulus oocyte complexes (COCs) were collected by aspiration of medium sized ovarian follicles (4-8 mm). COCs of acceptable quality were selected, washed and incubated in tissue culture media 199 (TCM199) supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal calf serum, 5 μg/ml luteinizing hormone (LH), 0.5 μg/ml follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and 1 μg/ml estradiol-17β for 20:22 hour at 38.5 C◦ under 5% CO2 in air with 90% humidity. different concentrations of LC (1.25,2.5 and 5mM) were used. The results were consistent for both maturation and fertilization and there is a significant increase in maturation, fertilization., cleavage and blastocyst rate. In conclusion, LC has important role in IVEP through addition of LC to maturation media or culture media it improved nuclear maturation and blastocyst formation rates in bovine oocytes.

Author Contributions

Academic Editor: John Okyere, CrossGen Limited.

Checked for plagiarism: Yes

Review by: Single-blind

Copyright © 2025 Nada Mohsen, et al.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Citation:

Introduction

Egypt is known as one of the oldest agricultural civilizations; the River Nile allowed a sedentary agricultural society to develop thousands of years ago Livestock form an important component of the agricultural sector for milk, meat 1, 2, 3, 4. The in vitro produced embryo could play a central role in dairy and beef production systems. Genetic selection and crossbreeding schemes can be optimized through strategies involving use of in vitro-produced embryos. In addition, prospects exist for using in vitro produced embryos to improve pregnancy rates in herds with low fertility 5, 6.

For effective fertilization and embryo production in mammals, both the nuclear maturation as well as cytoplasmic maturation of oocytes are important. The activation of pathways involved in protein synthesis and phosphorylation is indispensable for oocyte cytoplasmic maturation and subsequent embryo development 7, 8.

In vitro maturation (IVM) of oocytes is a promising technology for both the treatment of human infertility and in animal production as a means of improving genetic gain 5, 9. LC is a molecule which boosts fatty acids movement to the mitochondria through for ATP production. Thus, LC possesses a vital action in lipid metabolism. Furthermore, LC protects the live cells through free-radical-scavenger, and different antiapoptotic mechanism 10, 11. Adding LC in maturation or culture media improves oocyte’ maturation of oocytes5, 6. L-carnitine is a required co-factor for long-chain fatty acid oxidation because it generates long-chain acylcarnitines, which help move these molecules into the mitochondrial matrix. L-carnitine also controls pyruvate oxidation by serving as a substrate for the enzyme carnitine acetyltransferase (CrAT), which raises pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) activity 12.

Supplementation LC during IVM lead to increase maturation rate of oocytes. Furthermore, LC improved both cleavage and blastocysts rates, and greatly affected total number of blastocysts 13.

Material and Methods

The study was carried out at Animal Reproduction Research Institute - Giza, 12556 Al Ahram -Giza, 12111 Cairo – Egypt during the period from December 2022 to April 2023. The chemicals in this study will be purchased from Sigma Chemical Co (St. Louis, MO, USA). All experimental protocols have been approved (M/86) by the Committee for Research Ethics at the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine Mansoura University, Egypt.

Recovery of immature oocytes

Ovaries from apparently normal reproductive organs of heifers and cattle of unknown age and breeding history were collected within 30 minutes after slaughter and evisceration of animals at the private EL-Bagor abattoir. The ovaries were kept in a thermos flask containing warm normal saline and gentamycin. Then transported to the lab within 1-2 h after slaughtering according to the previous literatures 5, 6, 14.The ovaries were further washed as soon as we arrived to the lab in warm normal saline to remove the blood, debris and then kept in water bath at 37°C during oocyte collection. Before COCs selection by at least 1h, the maturation dish(s) is prepared by putting 100µl maturation media drops in sterile disposable petri dish then covered with mineral oil and incubated at 38.5 C◦ under 5% CO2 and 90% humidity 5, 15.

Using of 18-gauge needle attached to 10 ml syringe, medium sized follicles (3: 8 mm in diameter) were aspirated and pooled in a 15-ml conical tube16. After the end of aspiration, the tubes were left 10:15 minutes to allow follicular cells settlement. After sedimentation, about 5ml of sediment was recovered by dropper pipette and placed in 80 mm diameter sterile petri dish. COCs were selected using a stereomicroscope and transferred into another dish containing fresh pre-warmed TCM199 6, 14.

Classification of recovered cumulus oocytes complexes

The retrieved COCs were classified according to8, 17 into 4 grades based on their morphological appearance.

Grade A (good), COCs with six layers of dense compact cumulus cells investment and evenly granular homogenous ooplasm. Grade B (fair), similar to grade A, but with 2-4 layers cumulus cells. Grade C (poor), partially or completely denuded oocytes. Grade D (very poor), characterized by highly scattered cumulus cells and dark irregular ooplasm.

Grade A and Grade B COCs were washed three times in TCM199, followed by incubation under mineral oil in the same medium (10:15 oocytes/100 µl) for 22 h at 38.5 C◦ under 5% of CO2 in air with 90% humidity18.

Semen

Preparation of basic media and staining

Preparation of media and stock solution requests a sterile technique with exact and careful weighting of components. The use of a laminar flow cabinet is indispensable to evade any contamination that may alter and spoil the prepared media. An analytical balance with readability of at least 10 μg and accuracy of ± 0.1μg was used. All media were filtered using 0.2 μm (Millipore, USA) syringe filter and incubated for at least 2 h in a humidified atmosphere, 5% CO2 at 38.5°C before culturing the oocytes and spermatozoa5, 8. The medium used for oocyte IVM was tissue culture media 199 (TCM-199) supplemented with 10% heat inactivated Fetal Calf Serum (FCS), 5 μg/ml Luteinizing hormone (LH) 19, 0.5 μg/ml Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)20, 21 and 1 μg/ml estradiol-17β 22.The pH was adjusted to 7.45, 8. The basic media used for IVF was sperm Tyrode’s Albumin medium with Lactate and Pyruvate (sperm -TALP)23, and 20 µg/ml heparin sulfate is added to the media before filtration. The pH of the media is adjusted to 7.4. The medium used for culture is Modified synthetic oviductal fluid (MSOF) supplemented with 1 mM glutamine, 1% MEM (Eagle′s Minimum Essential Medium) essential amino acids, 0.5% MEM essential amino acids and 10% FCS was the In vitro culture medium (24). The pH was adjusted to 7.4. The selected COCs were randomly allocated to 4 maturation medium groups with different l carnitine concentration (0, 1.25mM, 2.5mM and 5mM). All COCs groups were matured, fixed and stained. Cumulus expansion rate was assessed.

Fixative, stain and stain removing agents are prepared according to25. Acetic acid- ethanol fixative (1:3 v/v)., Aceto-orcein stain: 1% (w/v) orcein stain in 45% acetic acid. Stain differentiation solution is acetic acid, distal water and glycerol (1:3:1 v/v/v).

Semen preparation and Oocyte insemination

Three straws of frozen semen were thawed for 30 sec. in 37C◦ water bath, evacuated in test tube. Swim-up technique, in modified-sperm TALP medium, was used for separation of motile sperm(26). Dilution of the final pellet of spermatozoa is made to obtain a sperm concentration of 2 million/ml as a final sperm cell concentration 27. 100 µl drops of sperm-TALP media containing spermatozoa is deposited in sterile disposable petri dish, and then covered with mineral oil incubated at 38.5 C◦ under 5% CO2 and 90% humidity.

Mature oocytes were washed three times in sperm-TALP then added to the fertilization drops, 10 oocytes in each drop. Gametes were co-incubated at 38.5 C◦ under 5% of CO2 and 90% humidity for 21 hrs. 27.

Inseminated oocyte culture

The culture dish is prepared by putting 50µl culture media drops in sterile disposable petri dish then covered with mineral oil and incubated at 38.5 C◦ under 5% of CO2 and 90% humidity. After 21hrs of gametes co-incubation, presumptive zygotes were removed from fertilization droplets. These zygotes washed three times in the culture medium. The presumptive zygotes (10 zygote/50 μl droplets) were cultured at 38.5 C◦ under 5% of CO2 and 90% humidity18. Semi replacement of the culture medium by fresh medium is done every 48 hrs. 24.

Maturation rate assessment

Fertilization rate assessment

Presumptive zygotes were fixed and stained with aceto-orcein stain 1%. Normal fertilization was indicated by presence of two pronuclei 25.

Cleavage and Blastocyst formation rate assessment

Embryos were assessed for cleavage 48 hours from the beginning of culture and further stages (morula and blastocyst) were checked approximately every 48 hours for up to 7 days. The embryo development rates were calculated according to 28 as follows:

Cleavage rate = no. of cleaved zygotes ×100/total no. of zygotes.

Morula rate = no. of morula ×100/total no. of zygotes.

Blastocyst rate = no. of blastocysts ×100/total no. of zygotes.

Fixation and staining method

Mature oocyte and fertilized oocytes were fixed and stained according to Mehmood et al. 201125.

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was at least three times replicated. According to Elmetwally et al.2018 and 2019 (29,30), the normality of quantitative parameters was tested using normal probability plots and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test created with SAS's UNIVARIATE technique. All experimental results are shown as mean SEM. The recovery rate, cleavage and maturation rate, and blastocyst rate are all represented as percentages. SAS® (version 9.2, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) will be used for statistical analyses. Differences will be judged significant when they reach (P ≤ 0.05).

Results

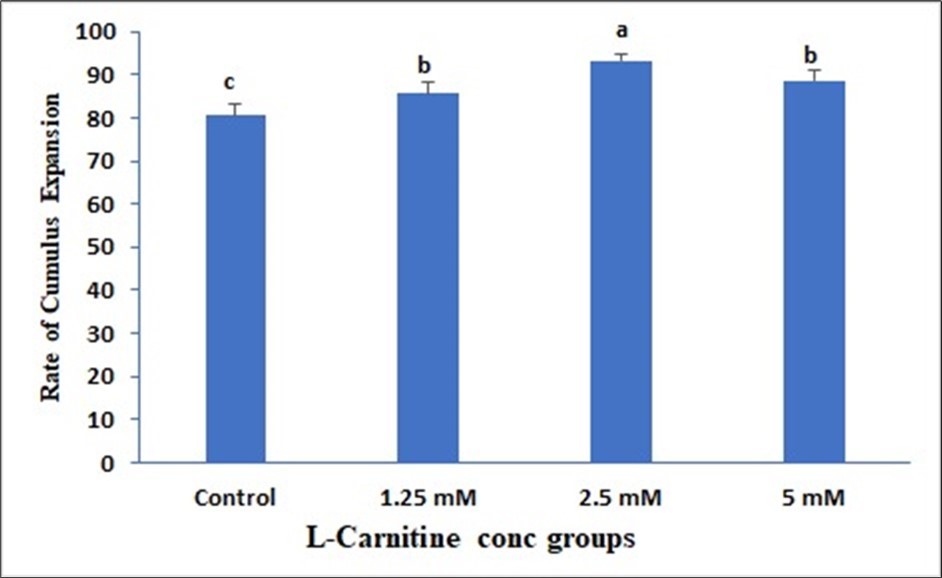

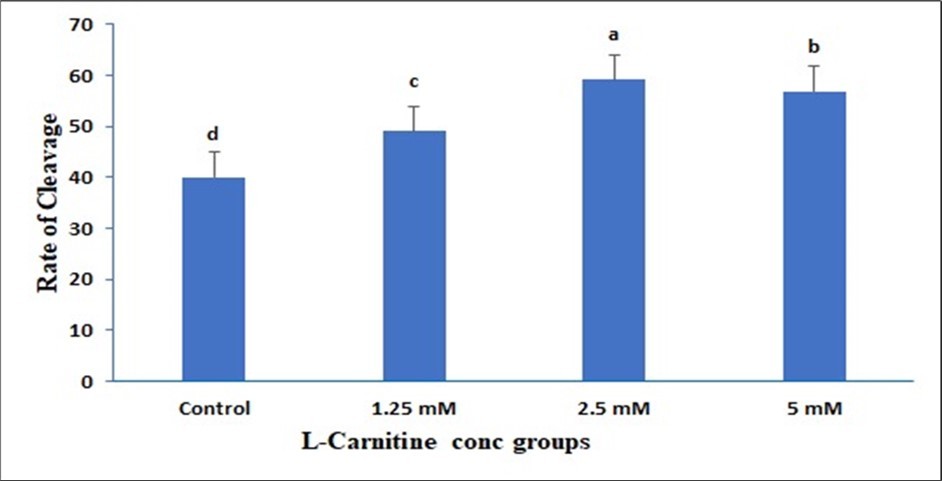

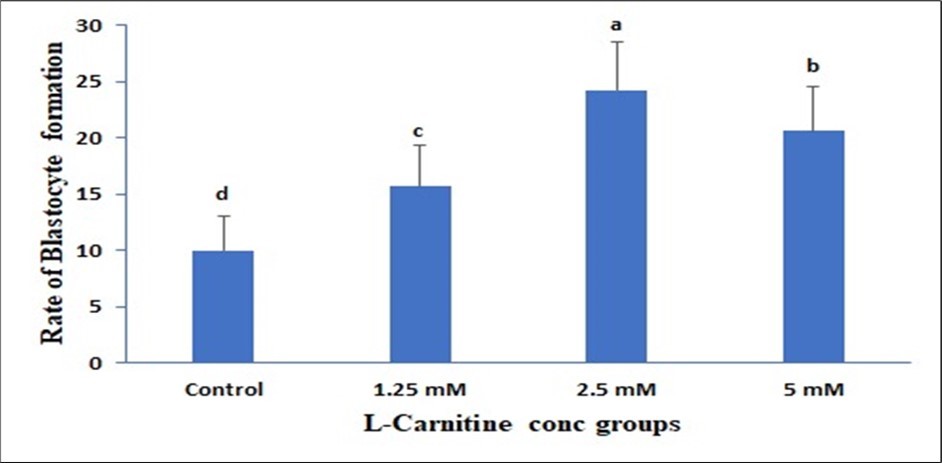

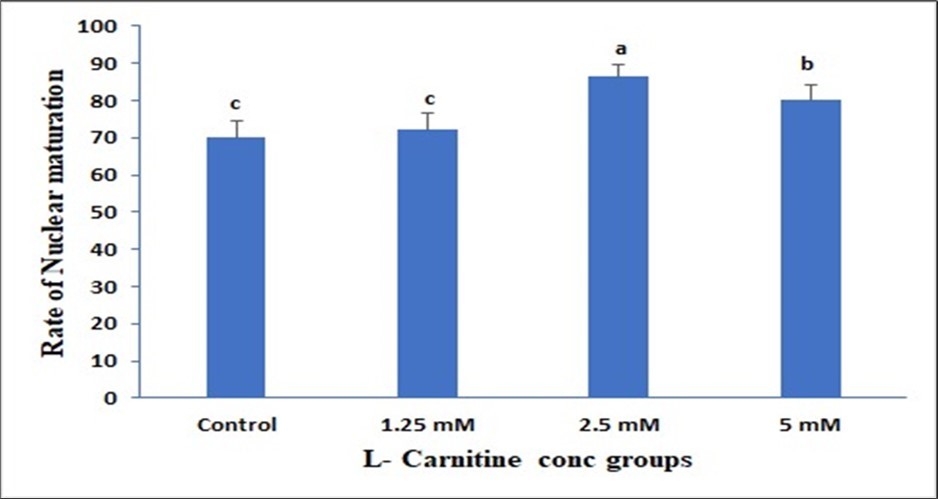

Data presented in (Figure 1) showed insignificant change in 1.25mM than control but a significant elevation in both 2.5mM and 5mM and the best one is 2.5mM due to LC supplementation on the Cumulus expansion rate. Data presented in (Figure 2) showed insignificant change in 1.25mM than control but a significant elevation in both 2.5mM and 5mM due to LC supplementation on the Cleavage rate. Data presented in (Figure 3) showed insignificant change in 1.25mM than control but a significant elevation in both 2.5 mM and 5mM due to LC supplementation on the Cleavage rate. Data presented in (Figure 4), in vitro maturation media supplementation with LC led to no significant change in 1.25mM than control but a significant elevation in both 2.5mM and 5mM when compared to control.

Figure 1.Effect of in vitro maturation media supplementation with l carnitine on the Cumulus expansion rate. Values with different superscript letters are significantly different (P<0.05).

Figure 2.Effect of in vitro maturation media supplementation with l carnitine on the Cleavage rate. Values with different superscript letters are significantly different (P<0.05).

Figure 3.Effect of in vitro maturation media supplementation with l carnitine on the Blastocyte formation. Values with various superscript letters are significantly different (P<0.05).

Figure 4.Effect of in vitro maturation media supplementation with l carnitine on the nuclear formation. Values with various superscript letters are significantly different (P<0.05).

Discussion

The culture conditions for oocyte maturation and embryonic development are critical determinants for the successful development of in vitro-produced embryos in a wide variety of mammalian species. In this study, the effects of an antioxidant (LC) treatment on oocyte maturation during IVM, embryonic development after PA and SCNT, and intracellular levels of GSH and ROS in oocytes were examined through a series of experiments. In addition, expression levels of several transcription factors and apoptosis-related genes were analyzed in SCNT embryos that were derived from LC-treated oocytes. Our findings demonstrated that treatment of bovine oocytes with LC during IVM effectively increased the intracellular level of GSH, scavenged ROS in oocytes, and stimulated embryonic development after PA and SCNT. In addition, LC increased the expression of POU5F1 and transcription factors, such as DNMT1, PCNA, and FGFR2 in SCNT pig embryos but showed no effect on the inhibition of apoptosis at the gene expression level 31.

Effect of in vitro maturation media supplementation with LC on the Cumulus expansion rate

The data of the present study the supplementation of the maturation media with 2.5 and 5 mM of LC induced a higher rate of cumulus expansion than the lower LC concentration as well as the control oocytes.

In previous studies indicating the beneficial effects of LC on maintenance of intracellular lipid droplets and the different microtubular structure. Accordingly, LC was proven to improve the process of cryopreservation of certain mammalian embryos and so far used as a repetitive procedure, the substantial differences of efficiency of this method depend on stage, species and origin of cells either produced in vivo or in vitro 5, 31. Factors that are supposed to cause most of these differences are the amount of intracellular lipid droplets and the different microtubular structure which leads to chilling injury in addition to the volume/surface ratio plays a crucial role for the cryoprotectant penetration32. The important impact of LC results from the mitigation of the harmful effects of vitrification on mitochondrial function, which lowers the competence of vitrified oocytes and results in ATP loss 33, 34. Animal cells produced more ATP when supplemented with LC 35, 36. LC regarded as a major beta-oxidation agent, facilitates the transfer of fatty acids from the cytosol to the mitochondria, hence promoting lipid metabolism within mammalian cells 37, 38.

So far, the metabolic activity plays a critical role in the developing embryo, preimplantation embryo development in mammals can be split into two phases: 1 the phase that is regulated by the proteins and mRNAs that accumulate in the oocyte and is marked by low metabolic activity, and 2 the phase that occurs after the embryonic genome is activated and is marked by a marked increase in metabolism concurrent with the formation and expansion of the blastocoel cavity. The transition of the embryo from the oviduct to the uterus is also linked to this alteration in the metabolic activity of the embryo 39. The success rate of in vitro embryo production (IVEP) has been significantly impacted by the study of these mechanisms, which has led to the development of culture media that take into account the metabolic needs of the embryo and the makeup of oviductal and uterine fluids 40.

All mammalian eggs are surrounded by a relatively thick glycoprotein layer called the zona pellucida which plays an important role during oogenesis, fertilization and preimplantation development 41. The mouse zona pellucida consists of three glycoproteins that are synthesized solely by growing oocytes and assembled into long fibrils. that constitutes a matrix. Zona pellucida glycoproteins are responsible for species-restricted binding of sperm to unfertilized eggs, inducing sperm to undergo acrosomal exocytosis, and preventing sperm from binding to fertilized eggs. Increasing maternal age and embryo culture conditions were adversely affected by the ZP elasticity and thinning which are essential for the hatching process 42, 43, 44. A thick ZP may be associated with low quality embryos 45, 46, 47.

Basically, the rate of glucose, pyruvate, lipid, and amino acid ingestion influences the synthesis of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) in embryo metabolism 48. Additionally, pyruvate and glucose are the main supplements added to culture media. But bovine embryos also contain stores of fat and glycogen. Though lipids, especially fatty acids, are the most abundant energy reserve in bovine embryos, the concentration of glycogen appears to be nearly nonexistent and is not well documented in the literature 6. In addition, when creating culture media for in vitro embryo formation, lipids as an energy source have not been considered. Triacylglycerol (TG) or free fatty acids are lipid chain macromolecules that are found in cells and act as energy storage. They are made up of long-chain hydrocarbons with a terminal carboxyl group 5, 40.

The beneficial effects of L carnitine supplementation to the IVM medium on the present study on the improvement of the oocyte expansion rate may be attributed to the ability of LC as well as the antioxidants, such as β-mercaptoethanol, cysteine, and cysteamine to stimulate the synthesis of intracellular GSH, which in turn has a crucial an antioxidative role and enhances viability of IVF produced embryos 49, 50. LC (β-hydroxy-γ-trimethylammoniumbutyric acid), an antioxidative agent, is known to have a beneficial role in cellular metabolism and embryonic development in mammalian species. LC protects cell membranes and DNA from damage induced by oxygen free radicals 51. In the same line, previous researches showed that the lower concentration from LC is associated with a significant improvement of immature bovine oocyte vitrification 52. Meanwhile, excessive LC concentration may result in reduction of lipid density which may be unfavorable to in vitro bovine embryo development 40.

Effect of in vitro maturation media supplementation with LC on the cleavage rate

In the current study, the supplementation of the maturation media with LC has a great impact on the cleavage rate of the immature bovine oocytes. The higher cleavage rate was investigated with the supplementation of the maturation media by 5 mM of LC when compared to the other concentrations of LC and control group. Furthermore, the other supplementation of the maturation media with other LC concentrations showed a significant rise in the cleavage rate of the immature bovine oocytes than the control group.

A possible explanation for this is that LC is a cofactor for lipid metabolism in animal cells, helping to move fatty acids from the cytosol to the mitochondria for firewood beta-oxidation. Previous studies have shown that using LC improved recovery and survival rates, as well as minimal abnormalities in the cytoplasm and zona pellucida when compared to controls 37, 38. Consequently, LC improved ATP production in animal cells 53. Similar results were investigated after adding LC to the IVM prior to vitrification on in vitro-matured calf oocytes52. On the other side, we published before that the supplementation of IVM with 1.2 mg LC increased the rate of zona pellucida abnormalities and cytoplasmic abnormalities and this may be attributed that excessive LC concentration may result in reduction of lipid density which may be unfavorable to in vitro bovine embryo development 40.

Further, the use of the basic media alone in vitrification of oocytes lead to decrease in maturation rate and developmental competence of vitrified oocytes as vitrification damages certain cytoplasmic components. Also, the vitrification of GV oocytes causes damage to the surrounding cumulus cells which consequently disrupts their communication with enclosed oocytes54. This communication is very important for successful completion of invitro maturation and subsequent embryonic development 6, so supplementation of the basic media of vitrification with LC avoided this damage55. The oxidative activity of mitochondria was mildly decreased by vitrification and drastically increased by LC adding to vitrification media in both mouse strains 56.

Similar to the current results, In vitro maturation (IVM) of pig oocytes causes active mitochondria to translocate from the cytoplasm's periphery to the cytoplasm's interior, or medullary area, according to previous observations 52. This process promotes embryonic development. Similar to this, the oocyte accelerated nuclear maturation, increased the number of active mitochondria, and lowered the levels of lipid droplets when the medium was supplemented with LC during in vitro maturation 52, 57, 58. Similarly, the inclusion of LC raised the percentage of embryos that hatched; this result was ascribed to an increase in the quality of the embryos and their capacity for development as a result of the lipid content being reduced 57, 58.

Effect of in vitro maturation media supplementation with LC on the Blastocyst formation and nuclear maturation

The culture conditions for oocyte maturation and embryonic development are critical determinants for the successful development of in vitro-produced embryos in a wide variety of mammalian species. In this study, the effects of an antioxidant (LC) treatment on the blastocyst formation and nuclear maturation during IVM of immature bovine oocytes was investigated 31. Previous studies proved that the LC affects the intracellular levels of GSH and ROS in oocytes and accordingly, improve the developmental competence of the bovine oocytes. In addition, there are expressions of several transcription factors and apoptosis-related genes in embryos that were derived from LC-treated oocytes 31.

The present results indicated that the supplementation of the maturation media with 2.5 and 5 mM of LC has a greater impact on the blastocyst formation as well as the nuclear maturation than the other LC concentrations and control treatment. In mammalian species, the antioxidant LC (β-hydroxy-γ-trimethylammoniumbutyric acid) is so far recognized to play a positive effect in cellular metabolism and embryonic development. DNA and cell membranes are shielded from oxygen free radical destruction by LC 59. The integrity of microtubule and chromosome structural integrity, as well as the amount of apoptosis, were significantly improved and lowered when mouse metaphase II (MII) oocytes and 8-cell embryos were cultured in a medium supplemented with LC (0.6 mg/mL)60.Furthermore, by lowering the levels of DNA damage and the inhibiting effects of actinomycin-D, hydrogen peroxide, and tumor necrosis factor-α on embryonic development, the addition of 0.3 mg/mL LC to culture medium enhanced the formation of blastocysts in mice 51.

In another study, it has been reported that the treatment of immature oocytes with LC during IVM resulted in enhanced preimplantation development of PA and SCNT embryos in pigs. Furthermore, other research reveals the favorable effects of L-carnitine on embryonic development in mice, bovine, and porcine49, 50, 51, 61. LC was successful in raising GSH levels in oocytes following IVM, but it had no effect on nuclear maturation 61. This finding suggested that LC advantageous effects were more pronounced on cytoplasmic maturation than on nuclear maturation. After PA and SCNT, this may have helped boost embryonic development even further 31.

The beneficial effects of LC in the current study may be attributed to its effects on the expression of DNMT1, PCNA, FGFR2, and POU5F1 mRNA levels in immature oocytes cultured in the IVM media supplementation with LC. Although the exact mechanism by which LC treatment raised mRNA levels is unknown, it is possible that cytoplasmic modification, including elevated GSH and decreased ROS activity, induced by LC treatment produced favorable microenvironments for donor nuclei's nuclear reprogramming and stimulated gene expression in cloned embryos 62, 63.

We also hypnotized the beneficial effects of LC may be attributed to its effects on the expression of the apoptotic proteins. Apoptosis is thought to be a normal mechanism that gets rid of cells that have chromosomal or DNA defects 49, 50. Nonetheless, loss of viability and failure to grow can result from an overabundance of apoptotic cells during embryonic development64, 65. LC functions as an antioxidant in animal cells or embryos and reduces apoptosis induced by oxidative stress by increasing intracellular GSH level and affecting mitochondrial functions. It has been reported that oxidative stress derived from ROS generation can induce apoptosis when oocytes or embryos are cultured in vitro 52, 64, 65, 66.

Previous studies have investigated that, the supplementation of IVM media with LC increased the expression of both pro-and anti-apoptotic genes; however, the pro-apoptotic gene (BAX) showed a greater increase in expression than the anti-apoptotic gene 31. Other studies showed that giving LC during IVM decreased the likelihood that parthenogenetic blastocysts in pigs would experience apoptotic nuclei 61. The cause of the proapoptotic gene's elevated expression was unknown, despite the fact that LC therapy benefited embryonic development and ROS levels were lower in IVM oocytes. Apoptosis is more common in capable oocytes from cycling gilts than in less competent oocytes from prepubertal gilts, according to a recent publication 67.

In summary, our results suggest that IVM treatment of oocytes with LC improves the cleavage, expansion, blastocyst and nuclear maturation and this may be regarding to the effects of LC on increasing intracellular GSH levels, reducing ROS toxicity, and regulating expression of POU5F1 and transcription factor(s) expression, which are necessary for the normal development of embryos.

References

- 1.Hussien A, Lenis Y SharawyH, James D, Turna O, Risha E.et al.(2021).The impact of differentestrussynchronization programs on postpartumholsteindairy cow reproductive performance. , Mans Vet Med 22(3), 124-30.

- 2.SharawyHA HegabAO, Risha E F, El-Adl M, Soliman W T, Gohar M A. (2022) The vaginal and uterine blood flow changes during theovsynchprogram and its impact on the pregnancy rates in Holstein dairy cows. BMC Vet Res. 18(1), 350.

- 3.Gohar M ElmetwallyM, Tawfik W, Rabie M SharawyH, Adlan F. (2023) Application ofcolordoppler ultrasound inegyptianbuffalo reproduction. NIDOC-ASRT. 54(4), 761-82.

- 4.SharawyHA HegabAO, ElmetwallyMA. (2023) Impact of the corpus luteum and follicular parameters on the levels of plasma progesterone and the prediction of pregnancy in Holstein dairy cows.ReprodDomestAnim. 58(11), 1525-31.

- 5.ElmetwallyMA MostagirAM, Bazer F W, Montaser A, Badr M, EldomanyW. (2022) Effects of L-carnitine andcryodeviceson the vitrification and developmental competence of invitro fertilized buffalo oocytes. J Hellenic Vet Med Soc. 73(2), 3961-70.

- 6.MostagirA ElmetwallyM.Montaser A,ZaabelS.(2019).Effects of L Carnitine and Cryoprotectants on Viability Rate of Immature Buffalo Oocytes in vitro After Vitrification. 62(2), 45.

- 7.KnitlovaD HulinskaP, JesetaM HanzalovaK, Kempisty B, MachatkovaM. (2017) Supplementation of l-carnitine during in vitro maturation improves embryo development from less competent bovine oocytes. Theriogenology. 15, 16-22.

- 8.Abdulkarim A, Badr M BalboulaA. (2021) Bedir W,ZaabelS. Comparing in vitro maturation rates in buffalo and cattle oocytes and evaluating the effect of cAMP modulators on maturation and subsequent developmental competence. Mans Vet Med J. 22(3), 136-40.

- 9.Dunning KR,RobkerRL.(2017).The role of l-carnitine during oocyte in vitro maturation: essential co-factor?. , AnimReprod 14(3), 469-75.

- 10.Kononov S U, Meyer J, Frahm J, Kersten S, Meyer U KluessJ. (2020) . Effects of Dietary L-Carnitine Supplementation on Platelets andErythrogramof Dairy Cows with Special Emphasis on Parturition. Dairy 2(1), 1-13.

- 11.Bucktrout R E, Ma N, Alharthi AS AboragahA, Liang Y, Lopreiato V. (2021) One-carbon, carnitine, and glutathione metabolism-related biomarkers inperipartalHolstein cows are altered byprepartalbody condition. J Dairy Sci. 104(3), 3403-17.

- 12.Muoio D M, Noland R C, Kovalik J-P, Seiler S E, Davies M N et al. (2012) Muscle-specific deletion of carnitine acetyltransferase compromises glucose tolerance and metabolic flexibility. CellMetab. 15(5), 764-77.

- 13.Omara S M. (2023) L-Carnitine Supplementation During In vitro Maturation of Egyptian Buffalo Oocytes Improved Embryo Yield and Decreased Blastocyst Apoptotic Rate. Pak.

- 14.Abdeldayem M, Badr M ZaabelS, SharawyH MostagirA, Adlan F. (2022) Effects of L arginine supplementation on in-vitro maturation and cryotolerance of immature buffalo oocyte. Mans Vet Med J. 0(0), 0-0.

- 15.Eldomany W, Hegab A, Monir A, Elmetwally M.Investigating the Effect of Dopamine on. in Vitro Maturation, Fertilization and Development of Immature Bovine Oocytes. JVHC 3(2), 1-15.

- 16.Raghu H M, Nandi S.Reddy SM.(2002).Follicle size and oocyte diameter in relation to developmental competence of buffalo oocytes in vitro.ReprodFertil. Dev.14(1–2): 55-61.

- 17.Helmy A, Halawa A, Montaser A, Tawfik W ZaabelS, Gohar M. (2023) The effects of fructose on the developmental competence, biochemical biomarkers and apoptotic gene expression by murine oocytes. NIDOC-ASRT. 54(3), 323-36.

- 18.Gasparrini B, A De Rosa, Attanasio L, Boccia L, R Di Palo et al. (2008) Influence of the duration of in vitro maturation and gamete co-incubation on the efficiency of in vitro embryo development in Italian Mediterranean buffalo (Bubalus bubalis). AnimReprodSci. May;105(3–4): 354-64.

- 19.Gasparrini B. (2002) In vitro embryo production in buffalo species: state of the art. Theriogenology. 57(1), 237-56.

- 20.Alves M F, Gonçalves R F, Palazzi EG PavãoDL.Souza F,QueirózRKR de, et al.(2013)Effect of heat stress on the maturation, fertilization and development rates ofin vitroproduced bovine embryos. 03(03), 174-8.

- 21.MHC Cruz, Saraiva N Z, Cruz JF da, Oliveira C S, Del Collado M et al. (2014) Effect of follicular fluid supplementation during in vitro maturation on total cell number in bovine blastocysts produced in. 43(3), 120-6.

- 22.Wang Z, Yu S, Xu Z. (2007) Effects of collection methods on recovery efficiency, maturation rate and subsequent embryonic developmental competence of oocytes inholsteincow. Asian-AustralasJ Anim Sci. 20(4), 496-500.

- 23.Parrish J J. (2014) Bovine in vitro fertilization: in vitro oocyte maturation and sperm capacitation with heparin. Theriogenology. 81(1), 67-73.

- 24.Badr MR.(2009).Effects of supplementation with amino acids on in vitro buffalo embryo development in defined culture media. , Global 3(5), 407-13.

- 25.Mehmood A, Anwar M, SMH Andrabi, Afzal M, SMS Naqvi. (2011) In vitro maturation and fertilization of buffalo oocytes: the effect of recovery and maturation methods. , Turkish Journal of Veterinary & Animal Sciences

- 26.Nandi S, Chauhan M S, Palta P. (1998) Influence of cumulus cells and sperm concentration on cleavage rate and subsequent embryonic development of buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) oocytes matured and fertilized in vitro. Theriogenology. 50(8), 1251-62.

- 27.Neglia G, Gasparrini B, V Caracciolo di Brienza, R Di Palo, Campanile G et al. (2003) Bovine and buffalo in vitro embryo production using oocytes derived from abattoir ovaries or collected by transvaginal follicle aspiration. Theriogenology. Mar;59(5–6): 1123-30.

- 28.Motility. (2009) acrosome integrity, membrane integrity and oocyte cleavage rate of sperm separated by swim-up orPercollgradient method from frozen-thawed buffalo semen. AnimReprodSci. Apr;111(2–4): 141-8.

- 29.Halawa AA ElmetwallyMA, Tang W, Wu G.Bazer FW.(2020).Effects of Bisphenol A on expression of genes related to amino acid transporters, insulin- like growth factor, aquaporin and amino acid release by porcine trophectoderm cells.ReprodToxicol. 96, 241-8.

- 30.ElmetwallyMA ElshopakeyGE, Eldesouky A EldomanyW, Samy A, Lenis Y Y. (2021) vaginal and placental blood flows increase with dynamic changes in serum metabolic parameters and oxidative stress across gestation in buffaloes.ReprodDomestAnim. 56(1), 142-52.

- 31.You J, Lee J, Hyun S-H, Lee E. (2012) L-carnitine treatment during oocyte maturation improves in vitro development of cloned pig embryos by influencing intracellular glutathione synthesis and embryonic gene expression. Theriogenology. 78(2), 235-43.

- 32.Vajta G, Holm P, Booth PJ KuwayamaM, Jacobsen H, Greve T. (1998) Open pulled straw (OPS) vitrification: A new way to reduce cryoinjuries of bovine ova and embryos. 51(1), 53-8.

- 33.Zhao X-M, Du W-H, Wang D, Hao H-S, Liu Y et al.et al.(2011).Recovery of mitochondrial function and endogenous antioxidant systems in vitrified bovine oocytes during extended in vitro culture. , MolReprodDev 78(12), 942-50.

- 34.Zhao X-M, Du W-H, Wang D, Hao H-S, Liu Y et al. (2011) Effect of cyclosporine pretreatment on mitochondrial function in vitrified bovine mature oocytes. Fertil Steril. 95(8), 2786-8.

- 35.Zare Z, MasteriFarahani R AbouhamzehB, Salehi M, Mohammadi M. (2017) Supplementation of L-carnitine during in vitro maturation of mouse oocytes affects expression of genes involved in oocyte and embryo competence: An experimental study. Int JReprodBiomed (Yazd). 15(12), 779-86.

- 36.Carrascal-Triana E ZoliniAM, A Ruiz de King, Hansen P J, Alves Torres CA, Block J.Effect of addition of l-carnitine to media for oocyte maturation and embryo culture on development and cryotolerance of bovine embryos produced in vitro. , Theriogenology 2019, 135-43.

- 37.ChankitisakulV SomfaiT, Inaba Y, Nagai T TechakumphuM. (2013) Supplementation of maturation medium with L-carnitine improves cryo-tolerance of bovine in vitro matured oocytes. Theriogenology. 79(4), 590-8.

- 38.Kerner J, Hoppel C. (2000) Fatty acid import into mitochondria.BiochimBiophysActa. 1486(1), 1-17.

- 39.Donnay I, Partridge R J.Leese HJ.(1999).Can embryo metabolism be used for selecting bovine embryos before transfer?ReprodNutrDev.39(5–6):. 523-33.

- 40.Sutton-McDowall M L, Feil D, Thompson JG RobkerRL, Dunning K R. (2012) Utilization of endogenous fatty acid stores for energy production in bovine preimplantation embryos. Theriogenology. 77(8), 1632-41.

- 42.Berkane N, Liere P, Hertig A OudinetJ-P, Lefèvre G, Pluchino N. (2017) From pregnancy to preeclampsia: A key role forestrogens.EndocrRev. 38(2), 123-44.

- 43.Cohen M, Bischof P. (2007) Factors regulating trophoblast invasion.GynecolObstetInvest. 64(3), 126-30.

- 45.Huang Z, Liu J, Gao L, Zhuan Q, Luo Y et al. (2019) The impacts of laser zona thinning on hatching and implantation of vitrified-warmed mouse embryos. Lasers Med Sci. 34(5), 939-45.

- 46.Liu C, Su K, Shang W, Ji H, Yuan C et al. (2020) Higher implantation and live birth rates with laser zona pellucida breaching than thinning in single frozen-thawed blastocyst transfer. Lasers Med Sci. 35(6), 1349-55.

- 47.Lu X, Liu Y, Cao X, Liu S-Y, Dong X. (2019) Laser-assisted hatching and clinical outcomes in frozen-thawed cleavage-embryo transfers of patients with previous repeated failure. Lasers Med Sci. 34(6), 1137-45.

- 48.Carrillo-González D F, Rodríguez-Osorio N, Long C R, Vásquez-Araque N A, Maldonado-Estrada J G. (2020) l-Carnitine Supplementation during. In Vitro Maturation and In Vitro Culture Does not Affect the Survival Rates after Vitrification and Warming but Alters Inf-T and ptgs2 GeneExpression. Int .

- 49.Dunning K R, Cashman K, Russell D L, Thompson J G, Norman R J et al. (2010) Beta-oxidation is essential for mouse oocyte developmental competence and early embryo development.BiolReprod. 83(6), 909-18.

- 50.Ye J, Li J, Yu Y, Wei Q, Deng W et al. (2010) L-carnitine attenuates oxidant injury in HK-2 cells via ROS-mitochondria pathway.RegulPept. 161(1), 58-66.

- 51.Abdelrazik H, Sharma R, Mahfouz R, Agarwal A. (2009) L-carnitine decreases DNA damage and improves the in vitro blastocyst development rate in mouse embryos. Fertil Steril. 91(2), 589-96.

- 52.SprícigoJF MoratóR, ArcaronsN YesteM, Dode M A, López-Bejar M.et al.(2017).Assessment of the effect of adding L-carnitine and/or resveratrol to maturation medium before vitrification on in vitro-matured calf oocytes. , Theriogenology 89, 47-57.

- 53.Vanella A, Russo A, Acquaviva R, Campisi A, C Di Giacomo et al.et al.(2000).L - propionyl-carnitine as superoxide scavenger, antioxidant, and DNA cleavage protector. 16(2), 99-104.

- 54.Ruppert-Lingham C J, Paynter S J, Godfrey J, Fuller B J, Shaw R W. (2003) Developmental potential of murine germinal vesicle stage cumulus-oocyte complexes following exposure todimethylsulphoxideor cryopreservation: loss of membrane integrity of cumulus cells after thawing. HumReprod. 18(2), 392-8.

- 55.Moawad AR El-ShalofyAS, Darwish G M, Ismail S T, ABA Badawy.Badr MR.(2017).Effect of different vitrification solutions andcryodeviceson viability and subsequent development of buffalo oocytes vitrified at the germinal vesicle (GV) stage. Cryobiology.74: 86–92

- 56.Moawad M, Hussein H A, Abd El-Ghani M, Darwish G, Badr M. (2019) Effects of cryoprotectants and cryoprotectant combinations on viability and maturation rates of Camelus dromedarius oocytes vitrified at germinal vesicle stage.ReprodDomestAnim. 54(1), 108-17.

- 57.Ghanem N, Salilew-Wondim D, Gad A, Tesfaye D, Tholen E PhatsaraC. (2011) Bovine blastocysts with developmental competence to term share similar expression of developmentally important genes although derived from different culture environments. Reproduction. 142(4), 551-64.

- 58.Harvey SC MandawalaAA, Roy T K, Fowler K E. (2016) Cryopreservation of animal oocytes and embryos: Current progress and future prospects. Theriogenology. 86(7), 1637-44.

- 59.Zhou X, Liu F, Zhai S.Effect of L-carnitine and/or L-acetyl-carnitine in nutrition treatment for male infertility: a systematic review. , Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2007, 383-90.

- 60.Mansour G, Abdelrazik H, Sharma R K, Radwan E, Falcone T et al. (2009) L-carnitine supplementation reduces oocyte cytoskeleton damage and embryo apoptosis induced by incubation in peritoneal fluid from patients with endometriosis. Fertil Steril. May;91(5Suppl): 2079-86.

- 61.Wu G Q, Jia B Y, Li J J, Fu X W, Zhou G B et al. (2011) L-carnitine enhances oocyte maturation and development of parthenogenetic embryos in pigs. Theriogenology. 76(5), 785-93.

- 62.Lee E, Lee S H, Kim S, Jeong Y W, Kim J H et al. (2006) Analysis of nuclear reprogramming in cloned miniature pig embryos by expression of. Oct-4 and Oct-4 related genes.BiochemBiophysRes Commun 348(4), 1419-28.

- 63.You J, Lee J, Kim J, Park J, Lee E. (2010) Post-fusion treatment with MG132 increases transcription factor expression in somatic cell nuclear transfer embryos in pigs. MolReprodDev. 77(2), 149-57.

- 64.AsimakiK VazakidouP, van Tol HTA, CHY Oei, Modder E A, vanDuursenMBM. (2022) Bovine in vitro oocyte maturation and embryo production used as a model for testing endocrine disrupting chemicals eliciting female reproductive toxicity withdiethylstilbestrolas a showcase compound. FrontToxicol. 24, 811285.