Conjunctival Resection for Mooren's Ulcer Refractory to Medical Therapy: A Case Report

Abstract

Purpose

To report a rare case of Mooren’s ulcer in a healthy young male without systemic autoimmune disease, and to highlight the effectiveness of conjunctival resection as therapy for cases unresponsive to medical management.

Case report

A 34-year-old immunocompetent male presented with progressive peripheral corneal ulceration in the left eye. Extensive systemic and infectious evaluations, including rheumatologic, immunologic, and microbiological testing, were unremarkable. Human leukocyte antigen genotyping was DR17(03)-negative and DQ2-positive. Rheumatological evaluation yielded no definitive systemic diagnosis. Despite immunosuppressive therapy with adjuvant medications, the epithelial defect and stromal inflammation persisted. The patient underwent conjunctival resection, resulting in marked reduction in inflammation, rapid re-epithelialization, and structural stabilization of the cornea. Histopathology of excised conjunctiva showed nonspecific inflammation without granulomatous changes, vasculitis, or neoplastic features. During follow-up, patient remained in remission with visual acuity preserved at 6/6 bilaterally and no recurrence.

Conclusion

Mooren’s ulcer is rare but vision-threatening. Early recognition, comprehensive evaluation, and timely surgical intervention can be vision-saving. This case highlights the role of a multidisciplinary approach and supports conjunctival resection as a useful adjunct in refractory disease. Long-term follow-up is essential.

Author Contributions

Academic Editor: Asaad Ghanem, Mansoura ophthalmic center, mansoura university, mansouraam

Checked for plagiarism: Yes

Review by: Single-blind

Copyright © 2026 Mahmood Al Noufali, et al.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Competing interests

There are no conflicts of interest.

Citation:

Introduction

Peripheral ulcerative keratitis is a rare vision-threatening disorder marked by peripheral corneal stromal thinning, epithelial ulceration, and adjacent tissue inflammation 1.

Unlike most cases with systemic triggers, Mooren’s ulcer lacks identifiable causes despite extensive workup, posing significant diagnostic and therapeutic challenges 2.

Treatment includes immunosuppression, but refractory cases may require surgical options such as conjunctival resection, which reduces local inflammatory mediators and helps stabilize the cornea 3. We present a rare case of unilateral Mooren’s ulcer in a healthy young male, unresponsive to medical therapy, but successfully managed with conjunctival resection.

Case report

A previously healthy 34-year-old man presented with two weeks of moderate pain, redness, tearing, and photophobia in the left eye. He denied any systemic symptoms, recent trauma, contact lens use or recent travel. Personal and family histories were unremarkable, with no known autoimmune, rheumatologic, or ocular disorders.

He reported a similar episode affecting the right eye three years earlier, presenting with three weeks of pain, redness, tearing, and photophobia. On examination, Snellen visual acuity (VA) was 6/6 in both eyes, with normal intraocular pressure (IOP), reactive pupils, and no lid abnormalities. Slit- lamp examination revealed marked conjunctival hyperemia, a faint whitish sclero-limbal infiltrate located inferonasally at the 6 o’clock position, associated with pericorneal vascularization and pronounced sectoral limbitis. The anterior chamber, lens and posterior segment were normal. Corneal scrapings yielded no microbial growth. He was diagnosed with marginal keratitis and managed with topical antibiotics, steroids, oral doxycycline and vitamin C. He improved over three weeks leaving only a very faint scar without recurrence until the current episode.

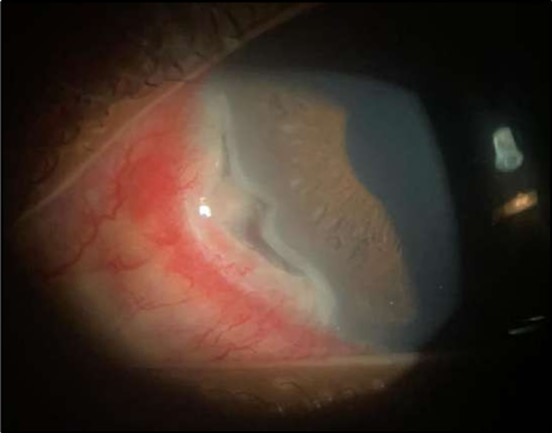

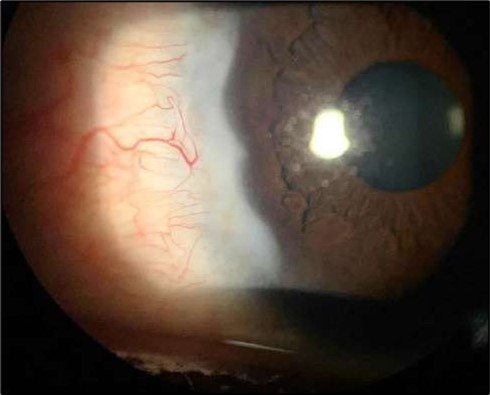

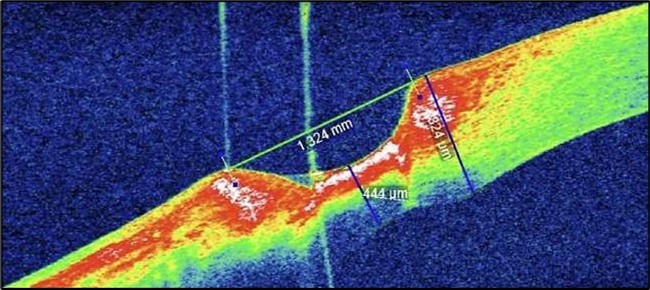

On the current presentation, Snellen VA was 6/6 in the right eye and 6/9 in the left eye, with normal IOP. The left eye demonstrated mild upper lid edema and intense nasal ciliary injection. Slit-lamp evaluation revealed a crescentic area of stromal corneal melting between 7 and 10 o’clock nasally, with overhanging edges and a fluorescein-positive base. No corneal infiltrates were present, and the surrounding stroma remained clear. The anterior chamber was deep and quiet, lens was transparent, pupil was round and reactive & normal posterior segment. Anterior segment optical coherence tomography (AS-OCT) confirmed a localized ulcer, measuring 1324 µm in horizontal width and extending to a depth of 380 μm, compared with an adjacent healthy corneal thickness of 824 µm, corresponding to approximately 46.1% stromal thinning (Figure 1a, Figure 1b, Figure 1c)

Figure 1a.Left eye (OS), on presentation. Slit-lamp image: crescent-shaped peripheral corneal ulceration located nasally, with severe adjacent conjunctival injection, peripheral thinning, and stromal infiltration.

Figure 1b.OS, Fluorescein-stained slit-lamp image: positive uptake at site of epithelial defect.

Figure 1c.Right eye (OD), Slit-lamp photo with a faint peripheral, inferonasal, small non-significant scar vascularization.

Comprehensive investigations excluded infectious and systemic autoimmune etiologies. Laboratory tests included complete blood count, C-reactive protein, renal, liver and thyroid function tests, glycated hemoglobin, urinalysis, and serologic testing for hepatitis B and C, human immunodeficiency virus, and syphilis. Autoimmune screening included rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibodies, anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies, cytoplasmic and perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (c-ANCA and p-ANCA), complement components C3 and C4, and serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) level. Additional investigations comprised the QuantiFERON-TB Gold test, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for herpes simplex virus, all these tests were normal. Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA)-B27 genotyping, and HLA class II genotyping, showed DR*17(03)-negative and DQ*02-positive status. Microbiological evaluation with gram stains and cultures of ocular swabs showed no growth, and chest radiography was unremarkable. Rheumatological consultation yielded no definitive autoimmune systemic diagnosis. Based on clinical features and negative workup, Mooren’s ulcer was diagnosed.

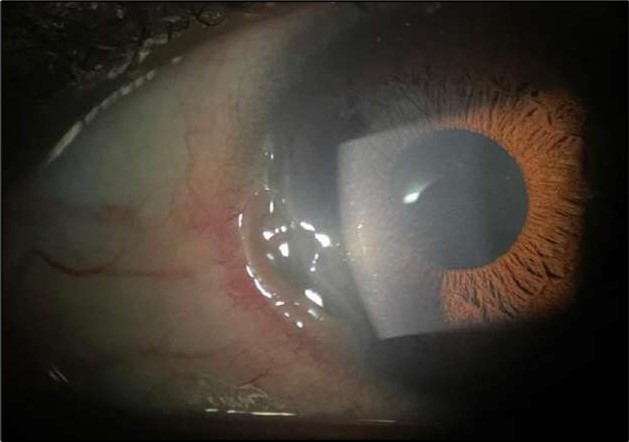

The patient was admitted and initiated on intravenous methylprednisolone 500 milligrams daily for three days, oral doxycycline 100 milligrams twice daily, oral vitamin C 500 milligrams twice daily, and a comprehensive topical regimen: moxifloxacin four times daily, fluorometholone four times daily, tacrolimus ointment three times daily, and preservative-free artificial tears. Gradual clinical improvement noticed over 72 hours, particularly in redness, inflammation and pain, but the epithelial defect persisted Figure 2.

Figure 2.OS, Slit-lamp image after a course of intravenous methylprednisolone therapy showing marked reduction in conjunctival hyperemia and stromal infiltration.

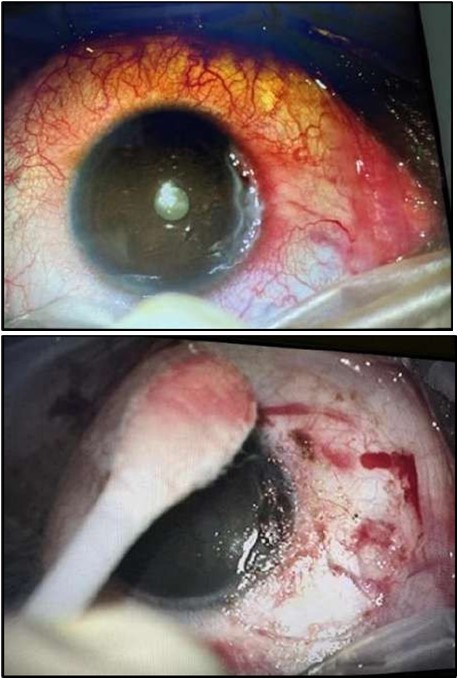

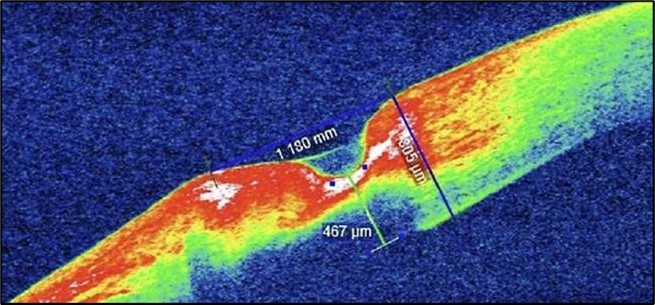

Despite systemic and topical management over one month, the epithelial defect persisted, indicating refractoriness to medical therapy. OCT imaging showed ulcer depth reduction to nearly 42% stromal thinning and width of 1180 µm, highlighting partial corneal healing. In view of the persistent ulcer and ongoing local inflammation, a conjunctival resection was performed to excise the perilimbal inflammatory focus and promote corneal repair Figure 3a and 3b.

Figure 3a and 3b.OS, Intraoperative photo showing excision of a 4 mm-wide strip of perilimbal conjunctiva between 7 and 10 o’clock, adjacent to the area of stromal ulceration.

Two weeks post-surgery, the left eye showed significant healing, with a small conjunctival granuloma and vascularization at the ulcer margins. The cornea was clear with a central leading edge nasally, deep and quiet anterior chamber and clear lens. VA 6/6 bilaterally and IOP normal. Histopathology of excised conjunctiva showed non-keratinized squamous epithelium with superficial erosions, stromal elastosis, hemorrhage, and inflammatory infiltration, but no signs of granulomatous disease, malignancy, or viral evidence, findings consistent with idiopathic localized inflammatory process. The patient reported significant relief and satisfaction post-surgery, resuming normal activities. Treatment continued with oral prednisolone 25 milligrams every other day, tobramycin-dexamethasone ointment twice daily, and preservative-free artificial tears four times daily Figure 4, Figure 5a, Figure 5b, Figure 5c, Figure 5d.

Figure 4.OS. Slit-lamp photograph showing a partially quiet ocular surface two weeks following surgical excision of adjacent perilimbal conjunctiva.

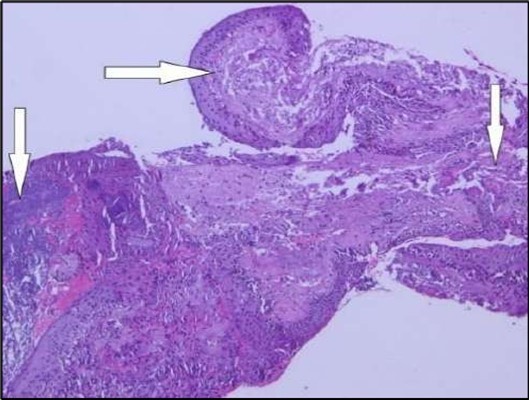

Figure 5a.OS, Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained section of the corneal specimen demonstrating full-thickness epithelial loss with underlying stromal necrosis.

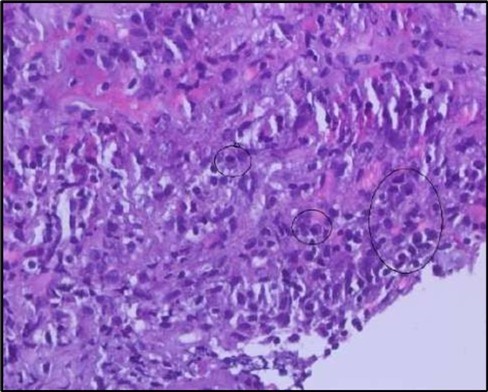

Figure 5b.OS, High-power H&E view showing dense inflammatory infiltration within the corneal stroma composed predominantly of lymphocytes and numerous plasma cells (circles highlight plasma cells).

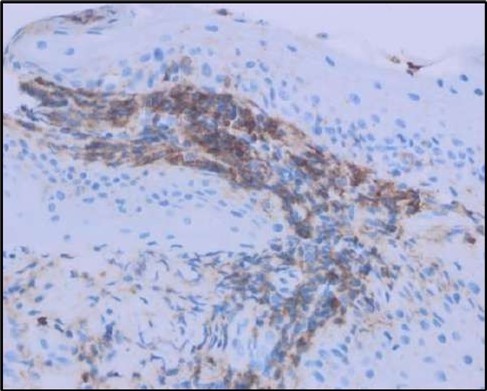

Figure 5c.OS, Immunohistochemical stain using CD45 (leukocyte common antigen) demonstrating a dense population of lymphocytes stained brown

Figure 5d.OS, Immunohistochemistry using CD138 showing many plasma cells (brown-stained) in the inflamed tissue.

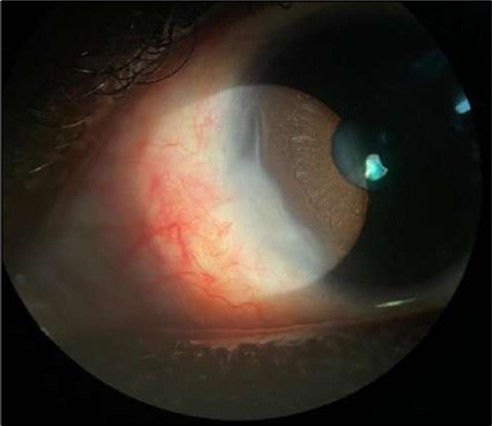

At six-months follow-up post-resection, the ulcer showed progressive epithelialization with no recurrence. Oral prednisolone was gradually tapered and stopped. The patient remains under regular ophthalmology follow-up with stable ocular findings Figure 6.

Figure 6.Six-month follow-up image showing a stable ocular surface, and absence of ulcer recurrence. The cornea appears clear centrally, with stromal scarring limited to the periphery.

Serial anterior segment OCT was employed throughout treatment to monitor corneal changes and response to interventions. Figure 7a, Figure 7b, Figure 7c, Figure 7d illustrate the ulcer’s progression: initial severity, minimal early response to medical therapy, post-operative healing after conjunctival resection, and sustained recovery at six-month follow-up.

Figure 7a.(At presentation): AS-OCT reveals a crescent-shaped peripheral corneal ulcer with marked stromal thinning of 380 µm in depth and complete loss of the overlying epithelium. The ulcer spans 1324 µm in width. The ulcer base appears concave with hyperreflective stromal margins, and a distinct overhanging edge is visible at the inner margin.

Figure 7b.(Following systemic immunosuppression): AS-OCT shows a reduction in ulcer depth to 338 µm and a narrower ulcer width of 1180 µm, suggesting minimal therapeutic response. The ulcer bed remains irregular with persistent stromal hyperreflectivity, likely due to ongoing inflammation. The overhanging edge is less prominent, and partial re-epithelialization is observed.

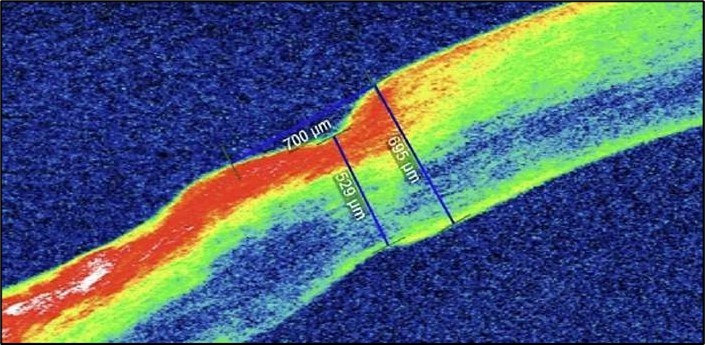

Figure 7c.(1-month post conjunctival resection): There is evidence of stromal remodeling with near-complete epithelial regeneration. The ulcer margins appear smoother, and stromal reflectivity is reduced, indicating diminished inflammation. The transition between the ulcerated and normal cornea is more gradual, consistent with active healing and fibrotic repair.

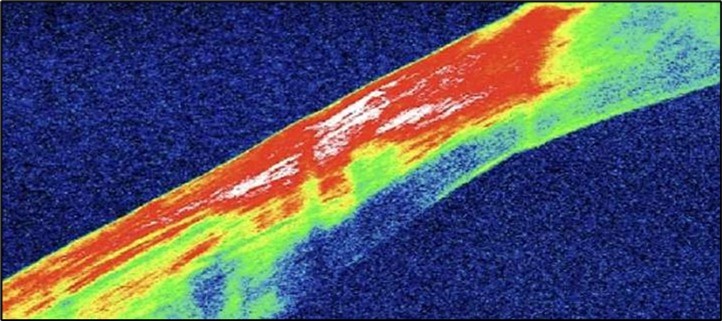

Figure 7d.(6 months follow-up): OCT demonstrates complete structural restoration of the cornea with a smooth anterior contour, full re-epithelialization, and resolution of the ulcer defect. Mild residual stromal hyperreflectivity remains, consistent with fibrotic scarring. There is no evidence of epithelial breakdown or recurrence, indicative of a quiescent disease state

Discussion

Peripheral ulcerative keratitis (PUK) is commonly associated with systemic autoimmune diseases, particularly rheumatoid arthritis and granulomatosis with polyangiitis, which together account for over 50% of cases 4. In some instances, it may even precede the diagnosis of a systemic condition, underscoring the importance of early systemic evaluation 5.

PUK is rare, with an annual incidence of 0.2–3.0 per million 6. Mooren’s ulcer shows marked geographic variation. It’s uncommon in Europe and North America, with tertiary centers reporting ~1 case/year, but more frequent in southern and central Africa and India with estimates ranging from 1 in 350 to 2,200 ophthalmic clinic visits 7.

In China, a large retrospective series reported 550 cases of Mooren’s ulcer over 36 years, corresponding to a prevalence of 0.03% of all ophthalmic clinic attendees 8. These disparities likely reflect environmental, infectious, immunological, genetic factors, and differences in access to specialist care.

Epidemiological data on PUK from the Arab Gulf are limited. Although isolated case series exist, comprehensive population-based studies on the prevalence and incidence especially of Mooren’s ulcer are lacking 9. Environmental factors such as high ultraviolet exposure and chronic sand or dust irritation may act as potential triggers for the breakdown of immune tolerance at the limbus in this region. This underscores the need for targeted research to define disease burden, distribution, and possible regional risk factors.

Mooren’s ulcer is an immune-mediated disease, involving the deposition of immune complexes in the limbal vascular arcades, activating the complement pathway, leading to perilimbal vasculitis 10. Subsequent inflammation induces chemotaxis of immune cells into the peripheral cornea, where they release pro-inflammatory cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) that hydrolyze stromal collagen, leading to stromal degradation, corneal thinning, and epithelial breakdown 11, 12. The peripheral cornea’s proximity to limbal vasculature facilitates immune cell infiltration, making it particularly vulnerable to these inflammatory processes 13.

Mooren’s ulcer shows no clinical or serological evidence of systemic autoimmune disease despite comprehensive evaluation 2. The localized nature of inflammation, coupled with the absence of systemic features, makes it a diagnostic challenge. A characteristic overhanging ulcer edge, considered a pathognomonic clinical feature, helps distinguish Mooren’s ulcer from other forms of peripheral ulcerative keratitis, in which the ulcer margins are typically sloped or undermined in a different pattern. Nevertheless, it may progress aggressively, leading to significant corneal damage and increased risk of perforation if not promptly addressed 14.

Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) genotyping in our patient showed DQ2 positivity and DR17(03) negativity, adding an interesting genetic perspective in Mooren’s ulcer. Prior studies linked Mooren’s ulcer with these alleles. Taylor et al. (2000) reported HLA-DR17(03) and/or DQ2 positivity in 83% of patients across a multinational cohort. In South India, HLA-DR17(03) and DQ2 were found in 40% and 45% of patients respectively, significantly higher than controls 15. Similarly, a Taiwanese cohort showed notable positivity for these alleles, with combined positivity rates nearing 79% when including data from Taylor’s non-white subgroup 16.

In our patient, absence of HLA-DR17(03) deviates from reported patterns, while HLA-DQ2 presence aligns with reported susceptibility markers. Although HLA-DQ2 is a relatively common allele associated with multiple systemic autoimmune disorders, including celiac disease, type 1 diabetes, and systemic lupus erythematosus, our patient exhibited no clinical suspicion or laboratory evidence of these conditions 17, 18, 19.

Nonetheless, HLA-DQ2 positivity may indicate a potential underlying, though subclinical, predisposition to autoimmunity, even in the absence of overt systemic disease. Collectively, these findings underscore the complexity and limited specificity of HLA associations in Mooren’s ulcer, reinforcing the need for broader population studies to clarify their clinical relevance.

Histopathological examination revealed a dense infiltration of CD138-positive plasma cells within the excised conjunctival tissue (Figure 5b, Figure 5c, Figure 5d). This finding supports an antibody-mediated immunopathogenesis in Mooren’s ulcer, consistent with Type II and Type III hypersensitivity mechanisms described in the literature 20, 21. The prominent presence of CD138- positive plasma cells provide a clear pathological rationale for conjunctival resection, as excision of the immunologically active perilimbal conjunctiva effectively removes the local 'factory' of autoantibodies that drive corneal stromal destruction, thereby halting ongoing tissue damage 21.

Standard management combines topical and systemic immunosuppressive therapies to halt the inflammatory cascade 3. Topical corticosteroids control early local inflammation but prolonged use risks corneal thinning, impaired healing, and stromal melting 22. Systemic agents address immune dysregulation and prevent progression or recurrence (Watson, 1997) 23. Adjuvant therapies included doxycycline and vitamin C. Doxycycline was used for its ability to inhibit MMPs, particularly MMP-9, thereby reducing stromal collagen degradation and limiting progressive corneal thinning. Vitamin C was administered to support stromal repair by promoting collagen synthesis and cross-linking, which are essential for corneal structural integrity 24, 25. In addition, topical tacrolimus ointment was selected as a steroid-sparing immunomodulatory agent due to its potent inhibition of T-cell activation through calcineurin blockade. Compared with cyclosporine, tacrolimus has demonstrated higher immunosuppressive potency and favorable ocular surface penetration, making it a useful alternative in immune-mediated conditions 26, 27

While no formal international guidelines specifically address Mooren’s ulcer, treatment strategies are guided by expert consensus and retrospective series involving autoimmune associated PUK 28, 25. A stepwise approach is recommended. Initial systemic corticosteroids rapidly suppress inflammation, followed by steroid-sparing agents such as methotrexate or mycophenolate for long-term control 29. Refractory or severe cases may require biologics like rituximab or infliximab. Adjunctive therapies include oral doxycycline and vitamin C (Höllhumer & Cook, 2022). Therapy is individualized based on severity and response.

Some cases remain refractory despite medical therapy, requiring surgical intervention to preserve corneal integrity and prevent further complications. Conjunctival resection, a well-established option, excises perilimbal conjunctiva, removing local immune triggers that drive stromal degradation. This reduces inflammation, promotes ulcer resolution, and may limit systemic immunosuppression 30, 31. In our patient, the nasal corneal ulcer persisted despite topical and systemic corticosteroids and adjuncts. Conjunctival resection subsequently performed, resulting in ulcer stabilization and complete epithelial healing. Histopathology showed nonspecific inflammation without granulomatous, viral, or neoplastic changes, consistent with Mooren’s ulcer.

When ulcer progresses despite medical therapy, surgical options may be considered depending on severity, depth, and perforation risk. These include conjunctival resection, amniotic membrane transplantation (AMT), corneal patch grafting, tectonic keratoplasty, conjunctival flaps, and tissue adhesives 25. Conjunctival resection is particularly effective in localized, non- perforated cases like ours, with a reported success rate in a range of 70–80%, especially when performed early 31. More invasive procedures such as corneal patch grafting or

tectonic keratoplasty, are reserved for severe stromal loss, descemetocele or perforation 32

In our patient, 42% stromal thinning (1180 µm), without descemetocele or perforation did not warrant these more invasive procedures.

Long-term follow-up is essential as Mooren’s ulcer may recur even after resolution. In a large cohort, cumulative recurrence risk was 10.4% at 6 months, 17.1% at 12 months, 22.5% at 24 months, 27.2% at 36 months, and 28.6% at 48 months 33. Regular monitoring allows early detection and timely initiation and adjustment of medical or surgical therapy.

Conclusion

This case highlights the value of timely surgical intervention in Mooren’s ulcer. When medical therapy fails, conjunctival resection can halt progression, reduce local inflammation, and preserve vision in localized, non-perforated thinning. Thorough systemic evaluation and multidisciplinary care are essential to exclude autoimmune disease. Long-term follow-up and patient education facilitate early detection of recurrences. Prospective studies and randomized trials are needed to establish standardized guidelines and optimize treatment strategies.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nill.

References

- 1.E A Kasparova. (2020) Peripheral ulcerative keratitis: clinical features and management. , Ophthalmology and Therapy 9(4), 1-12.

- 2.Jhanji V. (2011) Idiopathic peripheral ulcerative keratitis: clinical features and outcomes. , American Journal of Ophthalmology 151(1), 139-145.

- 3.Tauber J, Maza Sainz de la, Hoang-Xuan M, T, C S Foster. (1990) An analysis of therapeutic decision making regarding immunosuppressive chemotherapy for peripheral ulcerative keratitis. , Cornea 9(1), 66-73.

- 4.S L John. (1992) Peripheral ulcerative keratitis associated with rheumatoid arthritis and Wegener’s granulomatosis. , Eye (Lond) 6(6), 630-636.

- 5.R L Watkins. (2009) Peripheral ulcerative keratitis preceding systemic autoimmune diagnosis. , Arthritis Care & Research 61(9), 1298-1302.

- 6.McKibbin M, J D Isaacs, A J Morrell. (1999) Incidence of corneal melting in association with systemic disease in the Yorkshire Region. , British Journal of Ophthalmology 83(8), 941-943.

- 7.M E Zegans, Srinivasan M. (1998) Geographic variation in Mooren’s ulcer frequency. , Ophthalmology Clinics of North America 11(4), 667-679.

- 8.Chen X. (2000) Clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes of Mooren’s ulcer in China: a retrospective study of 550 cases. , Cornea 19(5), 625-631.

- 9.Kochhar S. (2022) Epidemiology and clinical profile of peripheral ulcerative keratitis in the Gulf region: a review. , International Ophthalmology 42(6), 1775-1782.

- 10.M R Dana, Qian Y, Hamrah P. (2000) Immunopathogenesis of peripheral ulcerativekeratitis. , Cornea 19(5), 625-643.

- 11.Geerling G. (1999) Matrix metalloproteinases and corneal disease. , Ophthalmology 106(10), 1974-1981.

- 12.V A Smith. (1999) Matrix metalloproteinases in keratolysis: relevance to corneal ulceration. , British Journal of Ophthalmology 83(9), 1006-1014.

- 13.Gomes J A P, M R Santhiago. (2021) Immune mechanisms in peripheral ulcerative keratitis. , Eye 35(2), 345-355.

- 14.Mishra D. (2017) Clinical course of idiopathic peripheral ulcerative keratitis. , Cornea 36(12), 1527-1533.

- 15.J R Zelefsky, J, J L Davis. (2008) HLA class II associations in South Indian patients with Mooren’s ulcer. , Cornea 27(2), 158-162.

- 16.W L Chen, Y M Chen, I J Wang, Y I Hou, F R Hu. (2002) HLA-DQ and HLA-DR genotypes in Taiwanese patients with Mooren’s ulcer. , American Journal of Ophthalmology 134(1), 54-59.

- 17.Megiorni F, Pizzuti A. (2012) HLA-DQ association with celiac disease: role of DQA1 and DQB1 alleles. , Autoimmunity Reviews 11(8), 602-606.

- 18.L M Sollid. (2002) Coeliac disease: dissecting a complex inflammatory disorder. , Nature Reviews Immunology 2(9), 647-655.

- 19.J A Noble, A M Valdes. (2011) Genetics of the HLA region in the prediction of type 1 diabetes. Current Diabetes Reports. 11(6), 533-542.

- 20.S I Brown, B J Mondino, B S Rabin. (1976) Autoimmune phenomena in Mooren’s ulcer. , American Journal of Ophthalmology 82(6), 835-840.

- 21.B J Mondino. (1988) Inflammatory diseases of the peripheral cornea. , Ophthalmology 95(4), 463-472.

- 22.Dutt S, Biswas J. (2011) Topical corticosteroid use in corneal melting conditions. , Indian Journal of Ophthalmology 59(4), 298-303.

- 23.Srinivasan S. (2007) Systemic immunosuppression in peripheral ulcerative keratitis. , Indian Journal of Ophthalmology 55(3), 181-186.

- 24.Smith V, S D Cook. (2004) Doxycycline in corneal ulceration: MMP inhibition. , Cornea 23(7), 693-696.

- 25.Gupta P. (2021) Supportive therapies in corneal ulceration: role of vitamin C and doxycycline. , Cornea 40(6), 750-758.

- 26.Kawashima M, Kawakita T, Tsubota K. (2010) Topical immunomodulatory therapy for severe ocular surface disease. , Cornea 29, 68-73.

- 28.Sharma N. (2013) Idiopathic peripheral ulcerative keratitis: treatment strategies and outcomes. , Eye 27(8), 931-939.

- 29.Maleki A, S M Elkhamary. (2024) Updates on systemic immunomodulation in peripheral ulcerative keratitis. , Vision (Basel) 2(4), 11.

- 30.S E Wilson. (1976) Conjunctival resection in the treatment of Mooren’s ulcer. , American Journal of Ophthalmology 82(4), 506-513.

- 31.O G Erikitola. (2016) Conjunctival resection for treatment of peripheral ulcerative keratitis: clinical outcomes. , Cornea 35(9), 1173-1178.

- 32.Gupta P. (2010) Surgical management of peripheral ulcerative keratitis. , Ophthalmology 117(2), 338-343.

- 33.Yang P. (2017) Clinical characteristics and risk factors of recurrent Mooren’s ulcer in East China. , Journal of Ophthalmology 4526754.

- 34.S I Brown, B J Mondino. (1980) Corneal transplantation for peripheral ulcerative keratitis. , American Journal of Ophthalmology 90(5), 636-640.